I love Longs Peak, and one of my unofficial missions is to climb a different route/season combination nearly every time I reach for the summit.

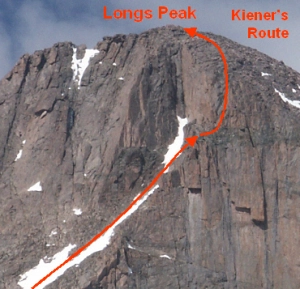

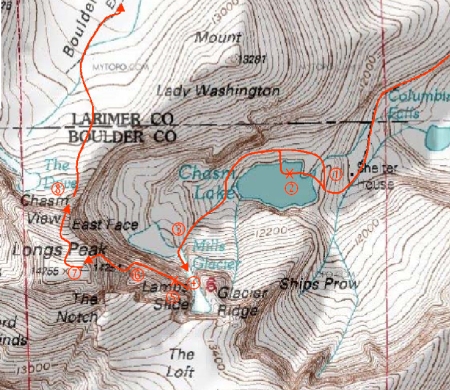

Next on the list was to reclimb the route used by the Stettner brothers (Joe & Paul) to climb Longs Peak on September 14, 1927, including the Stettner’s Ledges (5.8) route to climb from Mills Glacier to Broadway Ledge. As they did, we’d also use the Kiener’s Route (5.3) to skirt the difficulties of the Diamond and reach the summit. Stettner’s Ledges represented the hardest multi-pitch alpine route in Colorado (and perhaps in North America) for the subsequent 20 years.

“We were familiar with two established climbing routes on the East Wall — Kieners and Alexanders. We studied them. But we wanted to find a new route. We searched for a route by starting at Alexanders Chimney and working our way to the right with the binoculars. With the help of these field glasses, we found a line of broken plates, ledges, and cracks that we could eventually use as a route. It looked challenging enough for us.”

~ Joe Stettner’s Journal, recounting the events of September 14, 1927

On the morning of July 17, 1999, Brian and I started up the the trail towards Long Peak, passing the Longs Peak Ranger Station @ 4:15am. It would be my 6th different route to the summit of Longs Peak, if everything worked out. The only thing I worried about was the weather report; we’d have to get lucky to reach the summit on this day.

My Routes (prior to 7/99) to the Longs Peak Summit

- The Diamond, Casual Route (7/94)

- Notch Route (6/96)

- Keyhole Route (11/96)

- Kiener’s Route (7/98)

- Gorrell’s Traverse with a direct finish of The Notch (9/98)

The hike in went as so many have gone before it….long but tolerable. And, despite a serious attempt by a slippery trail to destroy my knee, we maintained a good pace and reached the foot of the climb by 7am. I somehow managed to forget that Mills Glacier would be hard snow and didn’t bring anything to aid my ascent of the glacier/snow field to reach the start of the Stettner’s Ledges climb.

Aiming for the bottom of the obvious left leaning flake system, I used my nut tool as a make-shift ice axe and kicked steps when I could and otherwise crawled to ascend the shockingly steep Mills Glacier. During this ridiculous episode, I stole a moment every now and again to think how this was a really stupid way to ruin a day, a season, or worse. My relief was palpable when I finally reached solid protection from a long slide to the bottom of Mills Glacier.

Stettner’s Ledges

1st Pitch

Brian took the first pitch. It was a 140-150′ long climb angling somewhat left over many flakes and cracks with a few pitons to guide the way. He found a nice ledge for our belay.

2nd Pitch

I took the second pitch that started with a step around a corner and involved easy climbing over some blocks to reach a good belay at a right facing large flake (5.5).

3rd Pitch

Looking up, we could see a series of pitons jammed into an overhanging dihedral protecting a steep climb over thin holds navigating a robust layer of slime. The water trickling down from The Notch was feeding an aquatic ecosystem that looked like it would be protected by Boulder’s Open Space & Mountain Parks organization if located a few miles further east. I tried to help Brian’s psyche by suggesting he could aid the climb if it was as bad as it looked. Right.

Not one for delaying the inevitable or waiting for government intervention, Brian took off to figure it out (in proper Paul Stettner fashion). After a moment of sitting, I noticed that the sun was gone; I was stuck in the shadows and my body temperature was dropping quickly.

I got small to preserve my body heat while I waited for Brian to swim up to the next belay and free me from my static duties. The conditions demanded a slow climb, but my suffering was all out of proportion to the hour it took for Brian to finish.

Climbers Rule of Variable Time Passage

“The rate at which time passes for a climber is directly proportional to the level of preoccupation for the climber and inversely proportional to the level of suffering and pain endured by the climber. “

And to make matter harder to endure, it was during this pitch that the rockfall barrage begain. I don’t know if it was climbers (I think it was although no one yelled, “rock” ) or merely natural falling rock from freeze/thaw action (the Stettner brother wrote of rock fall here in 1927), but it was damned unnerving to have such volume of rock crashing down the rock within 10 – 20 feet of my head.

When it was my turn to climb, I was so stiff and my hands so useless I didn’t think I could climb the 3rd Flatiron. But the body can warm up quickly when the stress is right. I followed Brian’s path through the slimy ecosystem, taking huge sections of it with me on my clothing. When I reached Brian, I could see he had taken a hit to his nose somehow. It was now a “blood” adventure.

4th Pitch

I traversed left onto the Lunch Ledge after mounting a steep flake system which felt harder than the rated 5.5. When I reached the end of the “Lunch Ledge”, it was obvious that we needed to make a team decision about how to proceed.

5th Pitch

I brought Brian up and then we took a few minutes to look for the direct line (Hornsby Direct variation). The rock was very confusing, and we just couldn’t spot the correct path out of the many options above us. We reasoned that we needed to hurry given the weather report and our plan to continue to the summit. We decided to find the easiest, quickest path to Broadway Ledge: The Alexander Chimney route. (Note: we also thought that this was the original line of the Stettner brothers, but that has since been refuted; the original line took a direct path, probably the Hornsby variation).

Even still, the path wasn’t obvious. Brian followed his nose, generally left and up over ledges and around corners.

6th Pitch

The final pitch was mine. I couldn’t figure out what I was looking for and eventually tried to climb a dihedral that didn’t quite work. After a downclimb I finally found something that looked like the Alexander’s Chimney finish, but ran out of rope without a belay spot in sight. I waited for Brian to take down the belay and then we simuclimbed the last 40 feet to Broadway Ledge.

It was a struggle, but we made it. And we did it without falls, but it took us 6.5 hours compared to the Stettner brothers 5 hours.

“With great trouble, we fought our way upwards. Time-wise, it appeared that we would have to retreat. The wall was approximately 1,600 feet high and, besides being steep, it had many overhanging sections.”

Yet, despite multiple falls held by a hemp rope (static) they bought at the Estes Park General Store (“Though not the best, it ought to fulfill the purpose”) that was merely tied around their waists, the Stettner brothers reached Broadway Ledge after 5 hours of climbing.

~ Joe Stettner’s Journal, recounting the events of September 14, 1927

Traverse to Kieners

We followed the Broadway Ledge to the Notch Couloir, and then to the far edge where we knew at least one variation of the Kiener’s Route that worked. We were on terrain we knew, but it was late on a day with a threatening weather forecast. But, with the weather still holding up well, we figured it was better to run up terrain we knew than to try to rappel down to Mills Glacier without a known rap route. And descending via Lambs Slide was completely out of the questions without crampons and axes.

Kiener’s Route

“Walter Kiener, a climbing guide, pieced together this route in 1924, looking for the easiest way up the east face with an eye toward future clients. Very little new ground was covered on the ascent. It’s possible he did this over several visits, with help from Agnes Vaille and Carl Blaurock. Another guide from this era, Guy C. Caldwell, installed cairns all the way up the route and advertised his services in the Aug 7, 1925 issue of the Estes Park paper”

~ Bernard Gillett, The Climbers Guide: High Peaks, 2nd edition (2001)

To save some time, we decided to simul-climb the low 5th class section.

We started straight up through the broken rock and over a chockstone, and then into a narrowing chimney which we took to its end, and, then, up a waterfall to a big, grassy ledge.

Past the 5th class climbing, we unroped to make fast time up the 700 feet of talus and gullies.

We knew from previous experience to aim for the edge of the face and look for the “Black Bands” of rock. When we finished climbing over the long section of giant steps, we moved to the edge of the Diamond to turn the corner and reach the east talus slopes.

And after scrambling the final 200 feet of talus, we reached the summit at 3:45pm; my 6th Longs Peak summit was in the bag. We had climbed the 1600′ of elevation between Broadway Ledge and the summit in 1 3/4 hours; its good to see we can pickup the speed if we have to do so.

Our weather luck had held out, but we still had to get down.

Descent

We chose the Cables Route, as always, for its direct approach to the Boulderfield. The path is easy to follow since we’d done several time before, except this time the path was blocked by a large snow patch covering the last 100 feet above the rappel anchors.

Crap.

Fortunately, this snow had been in the sun all day. But the terrain was steep enough that it wouldn’t take much of a slip to generate the speed needed for air travel. We carefully kicked steps and jammed exposed fingers into the snow…anything to get a little friction. By the time we found the first rap anchor, my fingers were frozen stiff.

Then it started to rain.

Combined with the approaching darkness, we didn’t need any additional encouragement to hurry once again. A quick pace down that death-march trail got us to the Ranger Station by 7:45pm for a 15.5 hour round trip.

The best adventures always include some amount of overcoming or dodging serious setback, such as:

- A smashed knee

- Missing ice gear

- Rock fall

- A bloody nose

- A route finding error

- Threatening weather

And this trip was a great one.