Summary

On October 12, 2002, Mark Muto and I attempted Casco (13908′), Frasco BM (13876′) and French (13940′) via the Casco-French Mountain Ridge Traverse. We succeeded in summiting on Casco and Frasco BM but had to retreat just 300 feet below the French Mountain summit. We hiked a total of 11 miles and gained approximately 4,400 feet in 14 hours.

The hours lost route-finding in the snow ate too deeply into the season-shortened day-light, forcing us to not only miss out on French, but also to hike back to camp in the dark for 1.5 hours on icy trails with only our wits and the fading yellow light of a single dying headlamp to guide us.

Our plan was too aggressive, given the poor conditions. And I made a rash decision that cost me the French Mountain summit.

The Story

On a rare bonus trip, Mark returned to Colorado from Chicago after only 3 months for more mountain abuse (earlier that year we did the 14ers: Sunshine, Redcloud & Handies). I wanted to bag more 14ers, but eventually chose French Mountain due to proximity, knowledge about trail access, and sweet revenge (see explanation below).

How I failed to climb French Mountain on my first attempt

Failed Attempt #1 on French Mountain.

During Labor Day weekend in 2001, my wife and I set out to climb French Mountain. Using a Dawson’s 14er guidebook info for Elbert & Massive, I pieced together a driving and hiking route for French Mountain. This poor base of information combined with missing signs and early morning thinking to mislead me into driving to the North Halfmoon Trailhead instead of stopping at the South Halfmoon Trailhead.

Despite the features not quite matching what I expected, they were close enough to allow me to believe I was in the right place (e.g., larger peak off to the SE, trail running SW following a creek, a mine at the end of the road) until it was too late. While I suspected I was not in the right place, it was not until I reached the summit of ‘Ol Unnamed 400’ short of the proper altitude that I knew for certain that I had screwed up.

I was angry at myself for not being more careful, and I vowed to atone for that error.

With Roach’s new (2001) 13er book in hand, I was able to quickly identify all the high 13er peaks in the area, and my desire to be efficient in collecting all the high 13ers led me to expand the day’s peak bagging goals. I broadened the plan to also include summiting on the Casco and Frasco BM on a traverse of the Casco-French ridge. But I should have been more focused on needs of the entire team.

Mark was a knowledgeable, but lightly experienced mountain climber; he was not in a position to know what set of goals/plans were possible & safe for him. He counted on me, as the more experienced climber, to pick a good & safe route. In the past, when Mark couldn’t finish due to illness or exhaustion, the “out and back” route plan allowed for him to simply wait for me to return. But on a “lollipop” route (stem with a loop on the end) with no escape routes, he HAD to finish the loop part of the route or retreat back to the start of the loop on his own if we were to separate.

It was a bad plan, especially in light of the variable conditions of the post-summer.

Leader Rule

In groups with unequal levels of experience, the most experienced person leads the group and is responsible for the safety of everyone in the group.

Day 1

I picked up Mark at DIA at 3pm on Friday, October 11 and we set off toward Leadville. We arrived at the Halfmoon campground around 5:30pm. Using Roach’s 13ers guidebook and a bit of deductive reasoning led us to the Halfmoon Creek Trailhead. The mileages didn’t seem to work and the signage was a bit different; but with my past (painful) experience in the area, we worked it out.

The creek water level was low enough for us to drive across the creek. We made camp 100 feet up the road on a nice flat area with ample parking. With just enough daylight to finish, we set up camp, prepared and ate dinner, and packed for the morning’s activities. Once in the tent, Mark and I played a few hands of gin (5-0 for Joe) and then turned in for the inevitable terrible night’s sleep.

Day 2

Alarms buzzing at 5:45am, we crawled out into the cold darkness. I asked Mark to save me a little hot water to warm my stomach as a chaser to my food bar. After a cup of hot water (did I say “a little”?) and a ½ liter of nearly frozen water, I was as ready as I was going to be and we set off toward the Iron Mike Mine. It was approximately 6:40pm.

We set a fairly brisk pace up South Halfmoon road. I am always surprised how fast Mark can hike during the initial hours of our adventures, since he lives at a 500 foot elevation and, as usual, had only 12 hours to acclimate; but, there would be a price to pay later. The road slides up between the north ridges of French and Elbert (only 2 miles apart), but darkness and trees limited the views. We arrived at the end of the driveable road (1/4 mile from the Iron Mike Mine ruins) at 8am, and could see that there was a lot more snow than we hoped. But at least the weather of the day, while cold, was perfectly clear and windless; Project French Mountain was a go!

The normal route (what Roach calls the “Francisco Classic”) begins

- North to the saddle (“Friscol”) below the South slopes of French Mountain, summits on French and returns to the saddle

- Traverses WSW to Frasco BM, where it turns SW toward “Fiascol” (the saddle between Frasco and Casco)(descent possible below Frasco BM)

- Follow the ridge south to Casco staying on or near the ridge line (no descent options)

- From Casco, turn SE and again follow the ridge to a descent via the NE slopes

- Complete the circle with a hike back to the road

But given the snow conditions and Mark’s probable level of fitness, I didn’t think this was the way for us to go. The standard route felt risky due to limited escape options on the 2nd half of the ridge traverse. Although I was late to being thoughtful, I reasoned it would be smarter to reverse the route and do the part with available escape option last, which would coincide with the time of day we’d need options for retreat due to darkness or exhaustion.

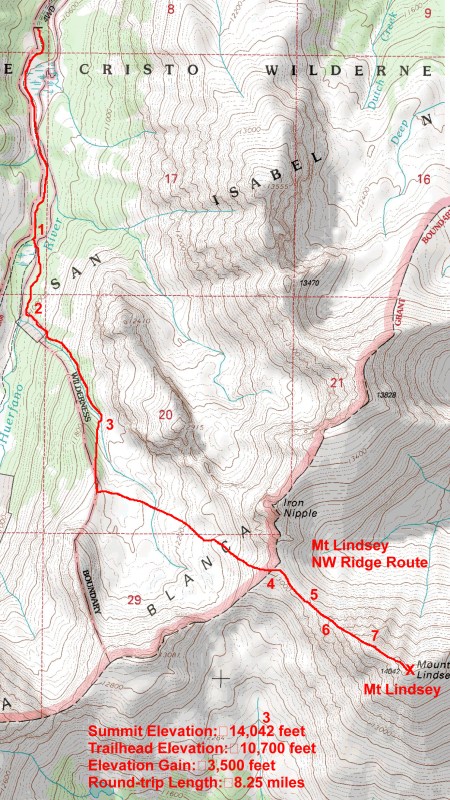

Our route sequence. Each numbered step corresponds to the description below.

Step 1

We turned south to mount the Casco ridge. Since we could not tell where the “NE Slopes” route was beneath the snow, we just headed straight up the slope.

The new snow was soft and deep enough to cause miserable hiking over unseen, loose scree. We stumbled over the increasingly steep terrain and climbed to the ridge with far more difficulty that expected. But Mark was continuing to move well; he even beat me to the ridge.

Step 2

Once on the ridge, we turned toward Casco. The hike up to the Casco summit was fairly easy as the snow was mostly clear of that part of the ridge (there was sharp contrast between the snow covered northerly facing slopes and the nearly snow-less southerly facing slopes). Arriving at the summit around noon, we stopped for lunch and a view.

From our rock bench, we could see La Plata to the south so clearly that we reminisced about a trip on La Plata a few years back. One that day, the very deep and soft snow made for an exhausting effort just to reach the peak. Mark made it to just below the north ridge when he began a vomiting and limb-jerking fit that cost him the summit. We could see the precise spot on the ridge where he waited for Brian, Larry and me to return down the ridge. He tells me on every visit how he wants to go back to La Plata and erase that defeat.

The memory of that experience reminded me to mentioned to Mark that if we had any doubt about finishing the traverse, we should retreat now; there would be no escape for many hours otherwise. He wouldn’t hear of it.

Step 3

As we started down toward Frasco BM, the generally northern facing ridge was as bad as I feared. Since the ridge is the only option, we hesitated only momentarily. And, almost as quickly, we were stopped. Sixty feet from the summit, we could not find a good line down the ridge.

We hunted around for cairns (none) or routes below the ridge (none). I told Mark that I would proceed ahead to try to force my way down the ridge. I started carefully (and slowly) working my way down over icy rock and into a snow-filled, narrow gully. A slip on this sequence of moves meant an 800′ tumble into the basin; I moved as carefully as a barefoot person escaping the kitchen after breaking a glass. Once in the gully, I scooted down on my butt for 25 feet to a steep 5-foot drop, over which I executed a controlled fall to reach the bottom. It led to a flat area and good terrain for a good ways ahead.

I called back to Mark that the route worked, but required his full attention; he followed and we had just spent 30 minutes to gain 150 feet. And, at that point, I didn’t think we could go back safely anymore; my exact thought was , “We cannot go back now; if we have to retreat we’re screwed.”

And then, after only another 100 feet, we were stopped again. The icy conditions on the ridge proper made for a slip-n-slide to death. We checked out every option twice and concluded that we had no choice but to descend down the east side of the ridge to skirt the dangerous section. We donned our crampons and traversed the steep east slope for 100 feet. The snow was unconsolidated, but we were able to feel around with our feet to find rock holds under the snow. With axes nearly useless in 6 inches of loose snow over loose rock, we used our hands to dig beneath the snow for holds.

This process got us to another good part of the ridge where could make good time with hand-free hiking. After a couple hundred feet of good ground, the ridge sloped downward dramatically toward what appeared to be a drop-off. My heart sank.

Step 4

With the pattern of increasingly dangerous terrain and conditions, I couldn’t imagine how we could work our way down the ridge this time. And since daylight was running short, I felt a strong urgency to just do something…so I made a rash decision. Rather than go as far as I could to see what was really possible, I just decided to assume it wouldn’t go and instead just work down one of the western rock & snow gullies and find a way over to the west side of the Fiasco Col (“Fiascol”). I knew it would be a significant detour that would certainly eat up most of the remaining daylight, but I was at least certain that it would work; I wouldn’t waste any time gathering information and thinking about what to do.

It was a poor decision born of stress. I should have gathered the easily available information that would have made a better decision possible. I should have gone as far as possible along the ridge to be sure we really needed a dramatically different course of action.

Jumping to Conclusions Fallacy

“Dicto Simpliciter” (jumping to conclusions) is an inductive reasoning fallacy defined by making sweeping statements or not bothering to gather sufficient data to validate conclusions.

The long detour involved a down climb of several hundred feet through steep, loose rock and snow, a traverse of several hundred feet and a re-climb (via snow and rock) to the top of Fiasco Col, which we reached around 4pm. The ridge might have been even harder, but I didn’t bother to find out before committing to an irreversible and time-consuming course of action. It took us 4 hours to travel 0.3 miles from the summit of Casco to the top of Fiasco Col.

Step 5

Looking back to toward Casco Peak and Fiascol

After regaining the ridge at the top of Fiascol, we stopped for a rest and to finish the rest of our water. I also took a moment to look up at the ridge line we just avoided. With our crampons and axes, we could have descended in about 30 minutes. But thinking about past mistakes was a task for later.

We were still in harm’s way, and the daylight was running out. We needed to summit Frasco-Benchmark since it was on the way to the only safe retreat route, and, if it was possible, I still wanted to bag French.

I was still feeling good, and was in fact fairly energized by the need to move quickly. Unfortunately, Mark was running out of steam.

Mark announced that he wasn’t sure he could continue; after a brief pause, I mentioned that we had to get to Frasco BM to get to a safe descent. I also reminded him that we only had a couple hours of light left and our headlamps were stashed by the road. Mark dug deep and we started up the ridge toward Frasco BM.

There was little snow on this part of the climb, but we still had to pick our way through the rocks and around the towers along the ridge. To save time and Mark’s energy, I moved ahead to find the best path, signalling to Mark which way to go. This process allowed us to make decent time reaching the Frasco BM summit and access to the Frascol escape route. My plan at this point was to let Mark descend the route below Frasco BM while I continued over to French before joining Mark at the Iron Mike Mine.

Step 6

From the summit of Frasco BM, I thought the escape route looked too steep for a tired climber to descend safely. I told Mark that I thought continuing along the ridge would be better for him. I was thinking that the remaining bit of ridge was an easy hike, and, if we moved fast enough, I could still bag French before dark.

But he insisted with the plan to descend immediately; I suppose he was feeling worse than he looked. Before he started down, I bargained with him by saying we’d stay together on the easy terrain to reach Friscol which would be a safe descent. At this point, I really was expecting the remaining traverse to be easy (I had spied it from Casco’s ridge). And I continued to hold a faint hope for having time to run up & down French before dark.

He paused and asked me how I knew the terrain was easy. I said I viewed it earlier in the day and that I would confirm it. I climbed the tower blocking our view of the ridge and could see that I was wrong. The remaining ridge was a rocky and snowy scramble involving a fair amount of route finding and the occasional hard move – not an easy walk. I felt my opportunity to bag French Mountain disappear like a hamburger left within reach of a Basset hound named Bella.

For some reason, Mark stilled agreed to go with me; and we moved together toward Friscol & French Mountain. In a comical sort of way, it was a tortoise race: the sun crept toward the horizon while we slowly worked over the ridge. We reached Friscol at 6pm; with a 6:30pm sunset, we had only minutes of daylight remaining.

Nearing the end of our traverse, a view back toward Casco Peak. Our route is marked in red.

Step 7

I looked up the 300 feet to the French summit in frustration, but knew I had no choice. We used the tongues of snow in the col to glissade most of the way to the basin. Glissading in October is a pleasant surprise, but the low temperature and late hour left the snow a bit rough on the pants. The day’s “butt work” left holes in my britches. After a fair bit of postholing to get through the basin, we reached the road and our stashed gear & water at 7pm, eleven hours after we left it.

The water had been blessed by the Sun during the day, and it was still fairly warm. It tasted like liquid gold (read: good). All that was left was for us to make it back to camp.

Step 8

After a short break, we set off down the road to the feeble glow of a 3/8’s waxing moon and dying embers of the sun. As we neared the trees we could no longer see our footing, so we stopped to pull out our headlamps, only to find that mine was DOA and Mark’s was dying.

What a day!

Lightless, I was a slave to Mark’s weak headlamp, which bobbed around like it was attached to a bobblehead doll. And shortly after, watching Mark sit on the ground suddenly and then performing my own twisting-and-jerking-like-a-bee-swarm-victim dance to avoid the same fate, I came to understand that the trail was icy.

After a bit of learning, we discovered how to spot ice in dim light; it was my best performance of the day.

Another 1.5 hours and it was over. Tired as we were, we still needed to change into dry clothing, prepare and consume food and water, and pack for the morning drive to the airport. We completed our duties by 9:30pm and turned in to enjoy being warm and still and, on occasion, being unconscious.

Day 3

Sunday morning was a cold 15 degrees. We packed and cleaned and blew on frozen fingers before finally heading into Leadville for some breakfast. It was a quiet crowd and, by comparison to Mark and I, a clean one. My first priority was the bathroom, as I had not enjoyed one for the last 48 hours. Winding my way through the crowded restaurant, I found the door and went in. It was so quiet, it felt like I was at the back of the church during a moment of prayer. It was the crux of the trip.

A few hours later, Mark and I made our dutiful visit to the downtown Denver REI shop, and then on to the airport. I always get a chuckle thinking of Mark getting on a packed plane, him sans shower for 2-3 days. It’s gotta be funny to see.

Sure, it was a fiasco, but another adventure was in the books. We bagged Casco & Frasco BM, but I failed to bag French Mountain once again. Yet, I learned an important lesson from the mistake I made of “jumping to the conclusion” to leave the ridge; I should have collected more information before committing to an irreversible course of action. I also learned new respect for the responsibilities of a trip leader.

And regarding French Mountain, I swore I wouldn’t fail again; and while it took 3 more years, when I got my 3rd chance, I didn’t fail (see 3rd Times a Charm). But truth be told, I did nearly fail again due to a continuing tendency to try to pack too much into a trip.

Casco - French Traverse Attempt Data

See all trip reports