It had been a long time since I had gone on a big expedition….long enough to only remember the good things. I was ready to hit the big mountains again when my friend, Joe, started talking about a trip to Bolivia to climb Huayna Potosi (19,974 ft) and Illimani (21,122 ft).

The Cordillera Real, or Royal Range, of the Bolivian Andes is a very popular area for mountaineers due to easy approaches, high altitudes, and only moderate difficulty. To succeed, we would need to overcome the obvious technical, acclimatization and logistical challenges in addition to gastro-intestinal illnesses, serious sleep deprivation, and the constant threat of having our possessions stolen. And, of course, we’d have to cough up a considerable amount of money. We really had to want it.

It all started in January, 1999, while watching the Denver Broncos on their way to repeating as Super Bowl Champions (right, a long time ago). Joe mentioned that he was going to sign on for a guided trip to climb mountains in Bolivia. He asked me to join him and I agreed. Unfortunately, it turned out that Joe’s intention was not yet certain.

During the following 2.5 months, we played an email game of “I’m not sending my deposit in until you do” and “something’s come up at work, I might not be able to go.” It really was quite a lesson in communication – I frequently misinterpreted Joe’s email messages. Below are some examples to illustrate my errors:

|

Email Message

|

What I Thought Joe Meant

|

What Joe Really Meant

|

|

“I am going to sign up this week”

|

I’m committed and will make it official by the weekend

|

It sure sounds good, but I like to keep my options open until the last minute

|

|

7 days later when I followed up…

|

|

“I just got approval from work – I’ll send in the application and check ASAP”

|

Finally, the last hurdle has been cleared. I’m making it official tonight, or tomorrow at the latest

|

Now that I know I can go, I just have to be sure that I want to go. I’ll start thinking about it real soon.

|

|

5 days later when I followed up…

|

|

“Actually, I will call the guide service today with a credit card number”

|

I will make it official before the end of today

|

I’ll send the guide service an email telling them that I really want a spot

|

|

1 day later when I followed up…

|

|

“I’m in and deposited as of this afternoon”

|

? (I didn’t dare guess)

|

It’s official

|

In the end, we committed.

The trip lasted 16 days, during which we climbed two mountains: Huayna Potosi (19,974 ft) and Illimani (21,122 ft). We spent six nights in La Paz, otherwise in tents near our mountain objectives. On the trip we had three US guides: Jethro, Cate, and Brian; one Bolivian guide, Eduardo; and nine other climbers: The two Joe’s (me and my friend), Terri and Ralph (a couple from Canada), Steve (the CEO), John (“Harvard”), Rob (the Air Traffic Controller), Brad (the Brain Surgeon), and Mark (“Sharpshooter”).

Day One

Overmap of flight to Bolivia and location of key destinations

We landed in La Paz, the highest altitude capital city in the world (12,000’), on the morning of May 10 after a day of travelling. The adventure had begun!

The flight was uneventful, but also a bit unfair. Joe and I used Frequent Flyer Miles to upgrade to first class and began our vacation a bit early. The thought of sitting all mashed-up in a tiny seat for 11 hours of flight time just shriveled me. Joe tried to level the experience a bit by sharing a serving of mixed nuts with our unfortunate Comrades in low class. I mean in Coach. It didn’t work.

It was still a long flight, but my excitement over the adventure erased the unpleasant memories from my mind.

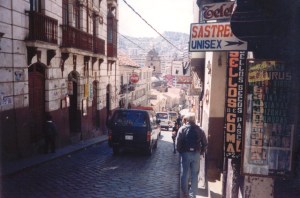

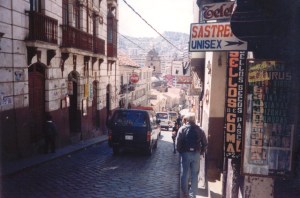

The airport is at 13,300’ elevation. Lugging my gear around at that altitude definitely felt unusual. We loaded our coach and drove down into La Paz; we came to understand that La Paz sits in a bowl surrounded by a high plain (called the Altiplano). The bottom of the bowl is protected from the high altitude weather and has very pleasant weather for a city at 12,000’. Our first order of business was to drive to our hotel in central La Paz and then keep ourselves busy to avoid the temptation of taking a nap (we didn’t get much sleep on the flight). Jetlag is a bitch even without drastic timezone changes.

Looking down into La Paz with Illimani off in the distance

Our first project was lunch, which resulted in Rob’s fanny pack, wallet, camera, etc. being stolen from under our noses in the Wall Street Café – a painful lesson that caused us all to be justifiably paranoid. Hell, we couldn’t even trust the water. We spent a great deal of effort acquiring “safe” water, but to no avail. Everyone was sick at some point and I was first. I spent the first night in the bathroom as my internal organs were liquefying and vaporizing as a result of being set on fire.

On the flight down, I had read up on what not to catch while in Bolivia. When you catch Giardia, the book instructed, you get huge amounts of intestinal gas, which comes out any way it can. In particular, I recalled that the virus is characterized by “farting out of your mouth.” I was sure I had it. But, instead, it passed (pardon me) and I felt well for the rest of the trip.

Day Two

The second day we traveled by coach to the highest navigable lake in the world – Lake Titicaca. I never did quite understand the full meaning of the word “navigable.”

nav·i·ga·ble (adj.)

Sufficiently deep or wide to provide passage for vessels: navigable waters; a navigable river.

Source: The American Heritage® Dictionary

I think the key word here is “…passage…” The lake must be good for moving between distant places, as opposed to a mountain lake in which you could use an inflatable raft to make your way around the shoreline. In any case, we sat on a few run-down 20-foot boats and “navigated” over to an island famous all over the world for building reed boats. I forget the name. Just kidding, it was called Suriqui. I understand the local Amayra Indians helped Thor Heyerdahl build the famous reed boats Ra II and Tigress for his exploratory expeditions.

The island of Suriqui....the reed boat builders

My primary mission for the day was to avoid the dry heaves (empty guts from night before). The island had visible remnants of ancient Inca agricultural production (the horizontal lines cut into the hills), but I especially enjoyed the views of the two peaks we’d be climbing, which were visible off in the distance.

Day Three

On the third day, three Jeeps arrived at the hotel to drive us up a dirt and rock road of death to reach the highest elevation ski resort in the world. Apparently, La Paz also has the highest golf course, football stadium, velodrome, and landing strip. And Burger King, too, I’ll bet.

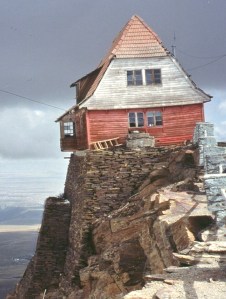

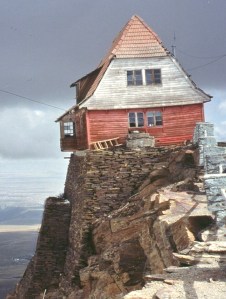

The "resort" hut

The so called ski “resort” had one ski run and a non-functioning towrope, but if you didn’t mind hiking you could ski. I suppose it was better than flying to Colorado for the day. At 16,000 feet, the idea was to help us to acclimate to higher altitudes while we practiced some basic snow travel techniques. We hiked a bit and then practiced our self-arrest technique.

The coolest part was the old hut that sat upon a pile of rocks. I only went inside because I didn’t notice the foundation until I came out again. It was a scary sight.

Day Four

On the fourth day, our effort on Huayna Potosi began. To climb Huayna Potosi, we would, on consecutive days:

- drive to Base Camp (15,500)

- train on the glacier below the mountain

- move to High Camp (17,700)

- climb to the summit (19,800)

- move back to Base Camp

- return to La Paz

A view of Huayna Potosi on the drive to base camp. In the foreground was a old graveyard for miners (I thought they said "climbers")

To our relief, it was a coach instead of a jeep that arrived at the hotel to drive us to the Huayna Potosi Base Camp. This drive was fun by comparison to the death road up to the ski resort. We had learned that whenever jeeps show up for transportation, we were in trouble

Huayna Potosi Basecamp

In Base Camp, we had a few chores before taking our acclimatization hike. First we set up the tents and then the latrine. The guides gathered the group together to explain that they would build a toilet out of rocks and place a plastic bag next to it for the used paper. After the hike, we settled in for our first of many games of Hearts. It was interesting to (re)discover how little I could do in a day at high altitude and be completely fulfilled as long as the day ended with a meal and an hour of playing Hearts.

During this time, Mark had decided to be the latrine’s first customer. A short while later while still within the walled area (ruins of a building) containing the latrine, Mark yells out, “where’s the plastic bag?” One of the guides, Brian, yells back, “it is right next to the toilet.” Mark responds, “there is no bag here, except the one you poop in.” Oops, Mr. Sharpshooter strikes. Apparently, on his last trip, Mark’s group was required to use a bag. We laughed unreasonably hard (…’til we cried, and then some); apparently there is nothing like high altitude combined with stress to make everything seem hysterically funny.

A view of Huayna Potosi from Basecamp.

Day Five

The fifth day was used to further our training and acclimatization. We hiked up to the glacier at the base of Huayna Potosi and practiced our cramponing and axe techniques. The training was very good as we used these skills continually during the summiting of Illimani without a single mishap. To reach the summit of Huayna Potosi we would not need much technical skill, just a lot of patience to endure the slow pace.

Day Six

The sixth day we moved up to High Camp at 17,000 feet.

When I was preparing for the trip back in Boulder, I read the trip brochure’s promise of using porters and pack animals “as much as possible” as a weak promise. So, my entire strategy in packing for the Bolivian trip was to bring a little as possible to reduce my pack weight to its minimum. I have suffered with heavy packs too many times to let that mistake eat away at my summit chances on a trip I paid so much to join.

The porters carried everything (e.g., sleeping bag, axe, crampons, helmet, food). I was amazed. I could not confirm that it happened, but I wouldn’t be surprised if one or more of the smaller clients hid away in the porters’ bags. So instead of feeling smart about a light pack, I had to dread how badly I would freeze high on the mountain and stink after 6 days in the same underwear!

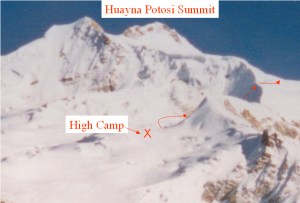

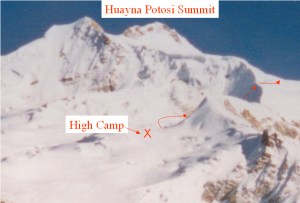

From High Camp, we ascende the headwall and moved to the far side of the summit to find the summit ridge

At High Camp, everyone was feeling a bit ill. My heart was pounding at around 90 beats per minute no matter what I did to relax.

The latrine at Base Camp was a luxury throne by comparison to the shit pit in High Camp. And, you had to watch out for pooping on your boot while you squatted over the hole dug in the snow.

Once the sun set, the only thing that mattered was getting in the sleeping bag. It got cold in a hurry.

Huayna Potosi High Camp

My light and highly compressible sleeping bag rated only to 5F instead of the recommended –20F. To compensate for the light insulation, I slept fully clothed.

This turned out to be a good idea, since I had to get out of bed every hour to pee anyway. I should have slept with my boots on to be even more efficient. I would later decide that a pee bottle is a great idea, after all these years of distain.

Day Seven

My heart stopped racing about midnight, and I managed to fall asleep about an hour before the guides woke us up on the seventh day to get ready for the summit push. When the alarm went out, I was so pumped I didn’t even feel tired. That would come later. When I stepped out of the tent, I could tell it was going to be a very cold morning. Wearing every bit of clothing I brought and still shivering – the only thing I could hope for was vigorous exercise.

From High Camp, we had to hike up the mountain in a somewhat spiral fashion to reach the summit. First, we had to climb toward the summit (north) for a short distance, then turn right (east) to mount a headwall, then back north past the summit to reach a ridge which we would take south (back toward High Camp) to the summit.

About 4am (yes, we were very slow; it was a big group and it was our first climbing day), we started hiking toward the Headwall. The Headwall was about 300 feet tall at a 50-60 degree angle. The snow was soft enough for us to gain purchase, so the angle didn’t matter as much. Of course, it was still cold, and at that point we were moving very slowly. We had a bit of trouble as the first few climbers tried to Jumar up the team rope (the rope we were tied into). They found out it is rather hard to pull yourself up a rope that is tied to the guy in front of you, but quickly corrected the mistake. Once we topped the Headwall, the sunrise was not far away.

Above the headwall and just after sunrise. The first team can be seen in the distance.

At sunrise, the temperature rose so quickly that I started sweating before we could take another break to shed some clothes. From the headwall, we climbed a rather flat section around to the backside of the mountain where we eventually crawled up a flat shoulder to the summit ridge. From there, we traversed 200 yards of knife-edged, wind blown snow to reach the summit.

The ridge traverse was quite stimulating. To the right, the snow angled at 85 degrees, falling away several thousand feet. To the left, the snow angled at 60 degrees initially and then 80 degrees, falling away 500 feet back to the shoulder we ascended. The snow on the ridge was a bit soft and tended to slide out from under your feet. The fixed line was a pleasure, to be sure.

The summit ridge. A slip to the left would cost you 500 feet; a slip to the right would take you all the way back to La Paz.

Due to the exposure, not all of the team would attempt the traverse. Mark had become too hypoxic to continue. During the ascent of the shoulder, he had been trying to name each step he took, but became frustrated when he couldn’t keep up the pace . . . Mary, John, uh . . Kim, uh . . . uh . . . Brian, uh . . oh damn! The team leader thought it would be best if Mark waited below the summit ridge as we pushed for the summit.

The summit itself was an angled hunk of snow atop a rock pinnacle. As the summit was so small and our group so big, there wasn’t enough room for all of us. As soon as the last man (me) reached the summit (and got off the ridge), the first team began to descend. While we waited for our turn, Joe and I took pictures with Cate and Edwardo, two of our guides, and looked off in the distance at Illimani, our next challenge.

The Joe's and Cate on the summit of Huayna Potosi with much of Bolivia in the background.

When our turn came, I took the lead for our rope team and followed the first team back down the ridge. Descending turned out to be a lot easier, as always. Our rope team made good time, and quickly caught up to the first team. They seemed stuck for some reason, an opportunity for photos that Joe and I didn’t miss. It turned out that Brad (the Brain Surgeon) had tripped and tumbled over the edge into the abyss. Fixed lines to the rescue! Soon Brad was back on the ridge and we all were moving again. Reaching the shoulder and Mark, we stopped for lunch and a rest.

The descent to High Camp with Basecamp in the distance on the far side of the lake. The first rope team can be seen standing above the Headwall.

The descent went slowly. The headwall provided some excitement, but mainly served to slow down my acquisition of additional water. I was very dehydrated by the time the team returned to High Camp. Once at High Camp, the Guides told us we were going to move to Base Camp. So, we packed up our gear and continued down the mountain. The hike out is always a death march, and this descent proved not to be an exception.

Me at Basecamp looking bad, but feeling pretty good. The sign referred to the electrical system powered by the dammed lake next to Basecamp.

At Base Camp, John (“Did I mention I went to Harvard”) and I collected water for the group and then helped set up camp before settling in to play Hearts. That night we went to bed early – I slept from 7pm to 7am, without getting up to pee once. It was a pleasure and a sure sign that I was dehydrated. And, Boy, did I need a shower!

Day Eight

On the eighth day, the coach eventually arrived to take us back to La Paz. While we waited, we sat in the sun and marveled at how much easier it was to breathe. My resting heart rate had fallen to 46 beats per minute, down from 90 during that first night at High Camp.

The drive to La Paz went quickly as we were entertained by a Bolivian soap opera on the onboard TV. Back at La Paz, we enjoyed showers and fresh clothes, the hotel steam room and pool, as well as some more of the local sites. I managed to wash some of the stink out of my clothes in the tub of my hotel room. As a side note, swimming underwater at 12,000 feet is a strangely panic-ridden experience….the oxygen in a breath of air just doesn’t last as long as it should.

The Witches Market

Day Nine

On the ninth day, we lost Mark. He said he had to go to Maui to meet his wife. It must be hard to be Mark.

Otherwise, it was an uneventful day during which we shopped in the Witches’ Market (Mercado de Hechiceria) and rested up for the next leg of our adventure.

Day Ten

On the tenth day, our effort on Illimani began.

Waitn' for the bus (or Jeeps in this case). From left to right was Steve, Brad, me & John

The mountain has four main peaks; the highest is the south summit, Nevado Illimani, which was our goal. To climb Illimani we would, on consecutive days, drive to Unna, below the massif of Illimani, and hike to Base Camp (14,000), move to the Mid camp site (16,000), hike to High Camp and return, move to the High Camp site (18,000), climb to the summit (21,122) and move camp back down to Base Camp, and finally hike back to Unna for transport to La Paz.

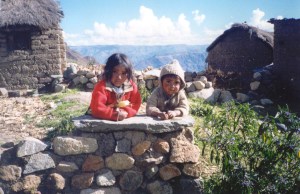

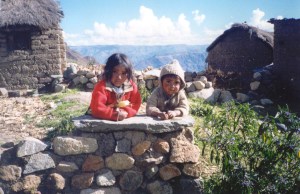

We hiked past a little village outside of Unna. The kids sure liked the candy one of our group was thoughful enough to bring.

When three Jeeps arrived to take us to the town of Unna, we knew we were in for a wild ride. The 4-hour drive dealt with paying special undocumented fees (some combination of bribes for police and extra pay for drivers) for using the roads, driving around washed out bridges, and getting past runaway bulls blocking the road, but we made it. Once in Unna, we left our gear to be carried up by the porters and pack mules, and we started hiking toward Illimani carrying only our fanny packs, with an objective of reaching Base Camp before dark.

Later, as we stopped for lunch, we watched the pack animals and porters go by us. The porters included a few older women, including one who was carrying my full pack and another full pack strapped to her back by a piece of cloth. I didn’t know how to feel. I was grateful, but also a little embarrassed. Those people are really strong and they really ‘work’ for a living; it was sharp reminder of how easy life is in the USA.

Base Camp was at 14,000 feet in a Llama field. It turned out to be the most comfortable campsite of the trip. The ground was soft turf, so our aching bones rested much easier. But it was also wet, so the air was exceptionally cold-feeling when the sun set. We learned it was best not to spend a lot of time outside in the dark, but we did try that first night. A late dinner that night included grilled cheese sandwiches, which turned out to be a favorite choice for all. The production rate was 4 sandwiches every 5 minutes, and we had 12 people who wanted at least 2 for dinner and could eat a sandwich in 1 minute. The math wasn’t pleasant; and jockeying for position at the grill was almost enough to distract our minds from the cold temperature.

Day Eleven

Day eleven was our ascent to mid-camp. Another 2,000 feet up a rocky road, then loose trail to reach the rock ridge leading to the High Camp. Somehow, this seemed to be the worst of our hikes. The combination of loose rock, hot weather and long approach combined to make it seem interminable. But, yes, we made it time for another round of Hearts.

Another round of Hearts, this time without oxygen

Day Twelve

The guides had talked us into using our extra (and unneeded, at that point) ‘weather’ day on day twelve to further our acclimatization. So, we woke up at first light and hiked 2000 feet up to High Camp to spend the day. This hike was more interesting than most ‘acclimatization hikes’ due to the exposure. High Camp turned out to be a crowded, little, flat bit of snow just to the side of the ridge leading to the summit. There was a French glacier scientific team of about 20 who seemed to be doing little measurement. There were also some British Columbia Canadians who were having a good time, eh. Of course, we spent the day playing Hearts and taking photos.

Back down to mid-camp, we enjoyed some free time. I wandered over to the latrine, which overlooked a valley to the side of the mountain. Since it was a hot afternoon, I had my shirt off already. Now I was sitting on this rock throne with my pants off too. It was one of the most freeing moments of my life to be buck naked with so much of the world visible to me. It was an experience that I will never forget. Then we played cards.

Day Thirteen

Jethro sittling below our climbing route on Illimani

On day thirteen, all we had to do was move to High Camp. We got a late start, but still made High Camp before any tent sites freed up. A large group was leaving soon, so we waited. During this time, we noticed that one of the members of that group was a beautiful woman . . . a beautiful, mountain climbing woman. A “mountain peanut,” as some of our group would say. Needless to say, we didn’t mind waiting as our minds were left to wander. Soon they left, and we were sad.

We set up camp quickly and enjoyed some Raman noodles for dinner. We went to bed early again, but this time I was careful to bring a pee bottle, and thank God I did. I pissed 3 quarts of liquid during a 7-hour period and I am still waiting for a letter from the people at the Guinness Book of World Records.

Day Fourteen

I slept much better this time as my heart stopped pounding earlier. When we were awakened, on day fourteen, the temperature was actually mild. I had to take off most of my fleece before starting the climb.

Our route on Illimani was to ascend the west ridge, while avoiding several crevasses and crossing a large berschund blocked the ridge. Most of the climb was high angle and in the dark until late morning.

The 3,300-foot climb started up a knife-edged ridge. In the dark, it is hard to see how far you might fall, but occasional glimpses added to the drama of the morning. Fairly early into the climb additional climbers abandoned, and the rest of the group (4 clients & 2 guides) reformed into a single rope team. We completed the ascent of the knife-edged ridge and then moved to the right to avoid open crevasses. We ascended a large, steep snowfield on the face of the mountain, and eventually moved back left to reach the easiest section of a Bergschrund. We reached the bergschrund at 10am and learned that this was somewhat above the ½ waypoint.

Crossing the bergschrund....and reaching for sunshine

The bergschrund was crossed via a naturally occurring ladder (it looked so old that it might have been from before the iron age) that Edwardo had hidden in the crevasse (he is the local guide). The ladder was kept from plunging off the mountain by a cord anchored to an ice screw. Still the ladder was unstable and climbing a ladder in crampons is not a natural act – it went slowly.

As last in line, I remained in the freezing cold shadows waiting my turn. While jumping and stomping my feet to stay warm, I could see the sunshine on the climbers as they reached the upper slope. I was looking forward to getting warm, and to easier climbing. Eventually, it was my turn and as I reached the pleasure of the sunshine, I looked up in horror to see that the climb got even harder. It looked dead vertical; I estimated the snow slope above me at 70 degrees (but you know how those estimate go). To lower the risk of a catastrophic fall, we used fixed lines until we reached the summit ridge, up and left from the top of the bergschrund crossing.

The summit ridge was technically easy, but nothing is really easy when you are hypoxic. I was not getting enough oxygen despite breathing as fast as I could (I foolishly refused to employ “pressure breathing”). Along the way, Edwardo pointed out the wreckage of a commercial airplane from a few years ago.

The Illimani summit ridge....just a few more steps! In the photo from left to right are Brad, Rob, John and then me.

The summit was glorious. We had made it in 7 hours – 500 feet an hour. Brad, John, Rob and I had summited on with Jethro and Edwardo. We all agreed that it was a significant achievement, despite Jethro’s warning that women would not be impressed.

Me on the Illimani summit (21,122') 5/23/99

The descent was quick by comparison, and much less scary; we reached High Camp in 2 hours. Back at High Camp, we were feeling pretty good for a 9-hour round trip at high altitude.

Unfortunately, the day’s work was not done. We still had to move to Base Camp. So, we packed up as much of the heavy gear as possible for the porters, and then began the 4,000-foot hike down the loose rock trail to Base Camp. On top of a 3,300′ ascent and descent, another 4,000 of descent made for a long day.

That night, I fell asleep early and slept through the night without interruption. On the soft Llama turf, it was the best sleep of the trip, if not my life.

Day Fifteen

On day fifteen, we had to hike back to Unna for transport back to La Paz. Base Camp was a cold place, but I didn’t want to be in warm clothes once the sun was shining. I dressed in shorts and began hiking quickly to stay warm. The combination of cold temperature and dehydration from the previous day conspired to keep me cold. I hiked as fast as I could to stay warm and reach the edge of the mountain’s shadow. My Sony Walkman (relax, IPods didn’t exist yet) kept me company until the sun got above the Illimani massif.

As we hiked, we could see that the porters/pack animals were not close behind us. Trying not to get to town too early (to avoid being mobbed by handout seekers), we took our time to reminisce and imagine new inventions that would be useful for climbers. Joe thought that a pill that would increase appetite would be good. Everyone agreed. (we all lost significant weight on the trip).

A wicked game of foosball distracted us from our delayed departure.

Finally back at Unna, we continued to wait for the behind-schedule porters. To pass the time, several of our group played on a foosball table at a cost of about 1-penny per game. In addition, Jethro tried to teach the local marble sharks a lesson, but lost his recently purchased marbles in the effort. Eventually, the equipment showed up and we left for La Paz and the Burger King we saw on the way out. I do believe that they make Whoppers out of filet mignon in Bolivia. The Burger King in La Paz seems to be the best in the world.

The #1 rated Burger King in the world, at least in my book.

To wrap up our fabulous trip, the guiding service took us out to dinner. It was a high end place that provided the sort of food we were used to eating back home; it had been a long trip filled with food bars & rehydrated food. It was a nice way to begin the transition back to the U.S.

Day Sixteen

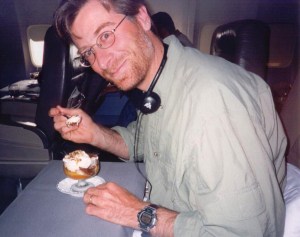

My buddy, Joe, takes a break from the beating in cards I gave him all the way home to enjoy some yummy ice cream.

Leaving La Paz was difficult.

Oh, sure, we wanted to leave. What I mean is the airport was ridiculously inefficient. First we had to wait in line forever to check in, then we had to wait in line to buy an ‘exit tax stamp’, then we had to get searched (read: felted up) by security for the stated purpose of ensuring we didn’t carry drugs, then we had to wait for the plane to board.

Well, the flight was good – first class again (see photo of ice cream sunday served). But it was a long travel day. We got up in La Paz at 3am (1am Denver time) to be ready for a 7am flight. We arrived in Denver at 11pm and got home after midnight – a 23-hour travel day.

It was a great trip, but I was glad to be home. All that was left was to shave off my scraggly beard and wash my seriously nasty clothes and gear.

See all trip reports