Mt Ypsilon and its Donner (left) and Blitzen (right) ridges

Blitzen Ridge. It has officially been on my Climbing Goals list since 1/1/2000.

Unofficially, it was added the day I climbed Ypsilon Mountain from Chapin Pass (a walk-up) and marveled at the majesty of the entire area on July 11, 1999 (see Mummy Range Weekend trip report).

One of the key problems in accomplishing this goal is I never get to see it; I’m always driving to Estes Park in the pre-dawn dark, and I’m always climbing in the Longs Peak, Glacier Gorge or Loch Vale areas which are far to the south. Out of sight, out of mind, I guess.

Still, every few years or so I’ve been reminded of it in some way. Each time, I mentioned it to Brian for consideration and always get a similar negative answer, all of which boil down to: too much hiking for too little climbing. The fact that this statement is essentially true led me to never push very hard.

But in the year, 2010, I decided I would finish a number of my long-standing goals. I started my lobbying efforts early, and was unintentionally aided by the fact that our climbing skills have fallen far enough to severely limit our RMNP alpine rock climbing options. Earlier in 2010, we’d done everything in RMNP we could think to do: Spearhead North Ridge, Notchtop Spiral Route, Hallet Great Chimney, Zowie Standard Route, Sharkstooth NE Arete, and we even bagged one of my long-standing goals, the Solitude Lake Cirque, a linkup of Arrowhead, McHenry, Powell and Thatchtop. And, so, with a perfect weather forecast, Saturday, September 4, 2010, was the time to dedicate ourselves, finally, joyfully, to climb Blitzen Ridge.

Interesting story about the first ascent and naming of Blitzen Ridge

On about Sept 1958, a group of Yale students did the first ascent of the Blitzen Ridge. After a forced bivy on the summit, they walked down to Fall River Pass (where the RMNP Alpine Center is located) in the morning and hitch-hiked down. They named the two ridges “Donder” and “Blitzen” intending the names to mean ‘thunder’ and ‘lightening’.

~from a Charles Ehlert email published by Andy in the Rockies

Oddly, the ‘Donder’ ridge is now named ‘Donner’. It is impossible not to recognize the reindeer names, and a little research revealed to me that naming of Santa’s raindeers has changed over the years. ‘Dunder and Blixem’ (Dutch) from the 1823 poem “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” (i.e., “twas the night before…”) by Henry Livingston, Jr. became ‘Donder and Blitzen’ in later versions by other authors, and eventually became ‘Donner and Blitzen’ in the 1923 song Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer. ‘Donner’ is the german word for ‘thunder’. Unfortunately, ‘Blitzen’ means ‘flash’ in german; it was used instead of ‘Blitz’ which is the german word for ‘lightning’ because of the need to rhyme with the name ‘Vixen’. Still, it works for me.

The Plan

The plan was a simple one, and was designed to finish the ridge climb with the least amount of hiking possible. It would also approximate the route used by the first ascent party in 1958, minus the hitchhiking.

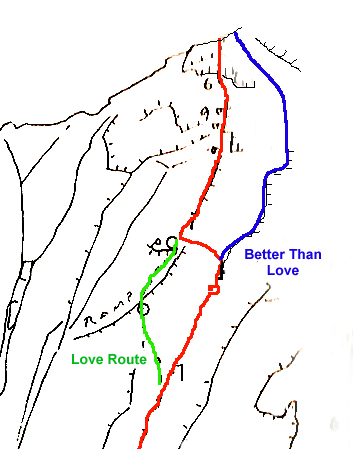

The Blitzen Ridge route map

We would start from the Lawn Lake trailhead at the bottom of Old Fall River Road and hike to the bottom of Blitzen Ridge via the Ypsilon Lake trail spur. We would climb the ridge and then descend from Ypsilon Mountain to Chapin Pass, where we would use a stashed vehicle to drive back to the starting point. Yeah, driving would save ~4 miles of hiking and scrambling, but it would still be a hard day: 10+ miles of hiking & climbing from the Lawn Lake Trailhead (8540′) to the summit of Ypsilon Mountain via Ypsilon Lake and Blitzen Ridge to cover over 5000′ of elevation gain in 12 hours.

“Opened in 1920, Old Fall River Road earned the distinction of being the first auto route in Rocky Mountain National Park offering access to the park’s high country.”

~nps.gov (http://www.nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/old_fall_river_road.htm)

I also hoped to check out the ‘Louis R. Leving Grave’ that is indicated on my GPS map as situated on the Blitzen Ridge.

On 2 August 1905, Louis Raymond Levings lost his life on the face of Ypsilon Peak…his body is buried there and a bronze tablet was erected where the body lies, to his memory.

~ Estes Park Archives

The Day

We met in Boulder @ 1am and drove up to RMNP in single file order. We drove past the Lawn Lake Trailhead at 2:10am on our way up Old Fall River Road to stash Brian’s truck at the Chapin Pass Trailhead. The road was in good shape, but still narrow and winding in places and so slow (and explaining why it is a one-way road). It took a little over 30 minutes to drive the 9 miles; then we dropped Brian’s truck at what seemed to be a parking spot (next to the sign forbidding overnight parking). We then continued up the one-way road in my 4Runner to the Alpine Center and then down the new Fall River Road to complete a 30 mile loop to reach, again, the bottom of Old Fall River Road and the Lawn Lake Trailhead.

And so it began.

Position 1

I was delighted to start on-time. I figured some part of my start-up plan wouldn’t work and we’d start late; I was glad to have the extra time. We actually arrived 20 minutes early. But my estimate of 1 hour to position the cars was actually low by 15 minutes, and that was with no traffic at all.

When we pulled into the Lawn Lake trailhead, the lot had half-a-dozen cars already parked. I couldn’t believe it; we wouldn’t be first on the rock. Brian suggested some of them might be headed toward Lawn Lake; I agreed it was good to have hope.

I had expected a cold, windy day, based on a forecast for Longs Peak on 14ers.com. But it was not cold, nor was it windy, except for the occasional gust. I packed away my extra clothes against the chance that the weather might change once we got above treeline. And at the last minute, to save on weight, I decided to leave behind my extra water and only bring 1 liter of water and an extra (empty) bottle. My plan was to drink a liter and refill both at Ypsilon Lake. I figured 3 liters would be too little water for a 12 hour hike & climb, but still enough to get me home.

Position 2

In my preparation for the trip, trying to remember my previous 3 visits many years ago, I couldn’t recall a cutoff for Ypsilon Lake from the Lawn Lake trail. I was worried that the Ypsilon Lake trail would be hard to find, and worried that not finding it would be a quick end to a long plan. I decided to bring my GPS primarily for the purpose of finding the cut-0ff in the pitch dark.

We started up the excellent Lawn Lake trail making good time in the pitch dark. At about 1 1/4 miles in, I pulled out my GPS to guide us. But it was all unnecessary. At 1.5 miles along the Lawn Lake trail, we came upon a small sign indicating the turnoff.

So far so good.

Position 3

The Ypsilon Lake trail started as a fine trail but eventually reminded me of the Knobs Shortcut to the Glacier Gorge trail; it was rough and dark. Still, I only lost the trail once as we worked our way past Chipmunk Lake and, finally, Ypsilon Lake at approximately 5am. In the dark, Chipmunk Lake looked like a swamp; Ypsilon Lake looked magnificent.

In my preparation research, I could not find any certain evidence of a ‘best’ way around Ypsilon Lake to reach Blitzen Ridge. Roach wrote of heading north from the east end of the lake, while Rossiter indicated to hike up a grassy gully on north side of the lake. I guessed ‘clockwise’ but wasn’t sure.

Once we arrived at the lake, I decided to take a couple minutes to see if a trail went counter-clockwise; it didn’t. And we did find a climbers trail to follow clockwise. The plan was still working. But at this point, I forgot to do something important.

Position 4

Our first view of Mt Ypsilon and the ‘Aces’ (see the shadows)

We followed the climber’s trail across a good bridge and for another 30 feet before completely losing all sign of a trail. We continued hoping to find a trail, but willing to bushwack our way eastward, moving up or down depending on the obstacles. I was looking for a talus field that was supposed to mark Rossiter’s ‘grassy gully’ that led to the start of the ridge. In the dark, the talus field we found 1/2 way around looked more like landslide debris; but we took it. It was very steep, but it went to the start of Blitzen Ridge, which we reached at 6am. Still on plan.

But then I realized that I had forgotten to get water at the lake. Shit. One liter of water for 12 hours of high altitude exercise = bad day. I started making an effort to breath through my nose instead of my mouth.

And, under the circumstances, I was glad to finally find the cooler temperatures and higher winds above treeline.

Position 5

It was still too dark to see any landmarks, but my GPS confirmed that we were on course. The next step was to follow the ridge as it turns from a rounded hill to a sharp-edged ridge. When we reached a point were we could see the Spectacle Lakes, the sun had come up enough to expose the scenery. Mt Ypsilon’s Y-Couloir and accompanying Donner and Blitzen Ridges are wildly spectacular; in my opinion, the area rivals Longs Peak, my favorite mountain in the world.

Brian examining the long way up Blitzen Ridge

The only odd thing was that we couldn’t see the Aces on the ridge. Eventually, we saw the shadows of the Aces on the Donner Ridge wall, highlighted by the morning sun. By 7am, we arrived at the base of the 1st Ace; it was an impressive pinnacle. To climb to the top of it would be a time-consuming undertaking.

Position 6

Our plan was to skirt the 1st two Aces. I took the 1st lead and did a descending traverse on 3rd and 4th class terrain to get below the 1st Ace and then continued with an ascending traverse over somewhat easier terrain to get by the 2nd Ace and to the base of the 3rd Ace.

Brian followed, arriving at 8am, and then prepared for his climb of the 3rd Ace.

Position 7

Brian’s lead of the 3rd Ace

The 3rd Ace was the one we had to climb, according to the route beta. Brian, delighted for a chance at some real climbing, worked his way up the 3rd Ace, taking the hardest path when possible.

When I followed, the route felt a bit harder than 5.4, but that made sense.

When I arrived at the top, Brian indicated that he couldn’t find a rappel anchor. Now that was a bother, as we brought two ropes specifically for the 2-rope rappel off the 3rd Ace.

I climbed out to the ridge edge to see if I could find an anchor or a place to set one without leaving iron behind; I couldn’t. The going was easy enough that I shouted to Brian that I was going to down climb and place gear to protect his down climb. I admit it would have been better if I had taken the rack; I only had the 5-6 pieces I cleaned from Brian’s lead.

I continued down until running out of rope, but I could see it was going to work. Brian followed and then we scrambled the rest of the way to the saddle between the 3rd and 4th Ace.

Position 8

The plan for the 4th Ace was to pass it on the right. I had read that the best path comes of climbing up for a bit before turning right. Looking at the 4th Ace from high on the 3rd Ace, I couldn’t make sense of this advice; and worse, the rock looked hard to climb. But once up close, the obvious weakness in the rock started up and right, right off the ground. It was my lead so I started up, following the slight ramp to see where it would lead.

The climbing was easy but the protection was scarce. I worked far enough right to see a probable path around the corner about 50 feet away. And then Brian yelled out that I only had 20 feet of rope left. Shit.

I brought Brian over and then he finished the climb by turning the corner to find a nice walking and scrambling path to the foot of the Headwall. He brought me over and then we scrambled to the Headwall, which would be Brian’s lead.

And then I forgot to look for the brass plate marking Louis Raymond Leving’s grave. Oh well, I guess it will wait for me.

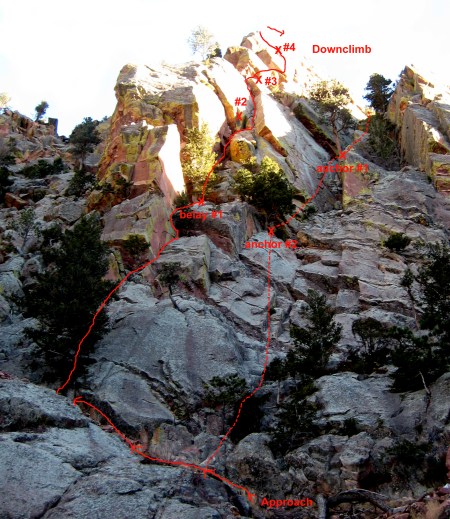

The Blitzen Ridge ‘Headwall’

Position 9

Brian indicated that he’d read that climbing the white pillar was the best start to the Headwall. I didn’t think he meant ‘easiest’…he didn’t.

Brian’s lead up the Headwall 1st pitch

He started up the SE corner and found the hardest climbing of the day. It was a balancey climb in a strong wind. I was surprised to be able to make it without a fall; I’m sure Brian was pleased with himself.

But we had another 125 feet of steep rock to reach the top of the Headwall. I ran the rope out 75 feet up some 4th class rock and then led a 50-foot pitch to reach the top of the Headwall near a notch in the ridge. Brian came up and then we unroped, based on the advice we’d read (but absolutely not based on the look of the rock).

Position 10

The first 50 feet or so were wickedly exposed, but the rock was good. The key was to get to the top of the ridge as quickly as possible. Once on the ridge, the difficulty was primarily past. It was mostly 2nd & 3rd class movement; the hardest part was avoiding the overhanging rocks just out of sight that jumped out to bash my helmet at any moment of weakness.

The last 100 feet was the easiest terrain since before the Aces.

Position 11

Ypsilon summit: enjoying our first break after 10 hours of hiking and climbing

I reached the summit at 1:30pm and sat down for my first official break of the day. I had saved 1/3 liter of water for my lunch. I was surprised that I didn’t feel dehydrated, but it had not been a hot day (so far, I should have realized).

I found Brian trying to use the sun to melt some found ice into his water bottle. We sat and chatted about the day; I insisted that the Blitzen Ridge was a great idea.

Brian asked if we were behind schedule; he thought I had mentioned a plan to summit at noon. The weather had been so good all day that I didn’t pay any attention to the time. I dug out my trip plan and found that our 7 hour climb was the high-end of my predicted range (5-7 hours). We decided to stay awhile and enjoy the views.

I claimed that we could have gone faster if we hadn’t tried to make the technical climbing portions interesting. I was probably right, but it was all good. A good climb and a good plan.

After a 30 minute break, it was time to head down; but not before stopping to appreciate our path over the many obstacles on the Blitzen Ridge.

Position 12

I had a mind to find the best compromise between shortest line between two points and avoiding losing any altitude that I’d have to re-climb. I followed a cairned path much of the way as I bypassed Chiquita and aimed for the saddle between Chiquita and Chapin, finding and losing the path at least a dozen times.

Brian had the energy to bag Chiquita on the way past. I skipped it since I had already done these peaks on my Mummy Range Weekend adventure some years ago.

Once at the saddle, the trail became excellent and we made good time back to Chapin Pass, finally seeing other people for the first time in the day. But it finally started getting hot, and I started feeling thirsty. I wished I had stashed some water in Brian’s truck; now I’d have to wait for the long ride through RMNP.

As we approached the trailhead, the sight of Brian’s truck (13 hours after leaving it) was a sight for sore feet.

We made it.

Panorama of descent path to Chapin Pass trailhead

All that was left was the drive back to my 4Runner at the Lawn Lake trailhead. Naturally, the traffic was horrific with all the tourists gawking at the aliens dressed as elk. But, as a mere passenger, I was permitted to sleep and catchup on the lost sleep of the night before (I only got 2 hours of sleep: 10pm to midnight).

And once back at my vehicle, I started home immediately, and I drank 2 liter of water as I drove home.

Another great trip.

Trip data (click for more details)

See all trip reports

See RMNP trip reports