It has been many years, but I can still remember my first visit to the summit of Green Mountain in the Boulder foothills in 1996 when I discovered the “mountain finder” placed at the summit by the Colorado Mountain Club in 1926. At the time, I only knew Longs Peak and Mt. Meeker, and learning the names of the visible peaks inspired a longing to explore them all. I was so happy to have moved to Colorado.

One peak was noteworthy for not being listed. It had a marker aimed at it, but did not have a name listed; I wondered why and vowed to find out. Unfortunately, my energy for the quest did not last, but, at least, the question did not fade from my memory.

In December, 2003, I was led by the nose to discover that the Indian Peaks Wilderness Area was a wonderful playground even closer to my home than my beloved RMNP. Naturally, I had heard of the Indian Peak and even noticed that many peaks in that area had Indian tribe names, but I was too busy with RMNP and other pursuits to worry about a bunch of 13ers. But when Brian and I were looking for some new terrain after 7 years of RMNP fun, Brian suggested Mt Audubon for a moderate hike we could do in winter.

And so a new habit began.

After Audubon, the ski season intervened to delay our return until April, when we did Apache via the Apache couloir (a Roach “classic” — 1000 feet of 45 degree snow). Hiking in and on the summit, we were amazed at the incredible climbing opportunities all around. Driven to do them as soon as possible, we returned the next week to climb Shoshoni via Pawnee Pass. On Pawnee Pass, we noticed a perfect looking little peak that sat in between Pawnee Pass and Paiute. It was time to buy a guidebook; and for our next visit, we would target Mt Toll.

Mt. Toll is described as a “classic” alpine route reaching a 13er summit by Roach (author of the Indian Peaks Guidebook). His opinion has long carried weight with me in his other books. Plus, there aren’t many of this type of route and we both were excited about some more high altitude climbing.

The next weekend we went up to Blue Lake below Mt Toll with our rock gear and found we couldn’t get to Mt Toll without snow climbing gear. We decided to use the day to go up Paiute instead. To reach the Paiute summit, Brian had to lead a pitch across steep, hard snow using just his nut tool while kicking marginal creases in the hard snow for footholds. It was spectacularly stupid. He made it.

As we sat on the Paiute summit and admired the ridge to Audubon and the spectacular North Ridge of Mt Toll, I still didn’t put two and two together. I still didn’t know how close I was to the answer of my Green Mountain question from 8 years earlier.

Mt. Toll via the North Ridge – A Classic Alpine Rock Route

Sunday, July 11, 2004 was the day we set aside for our 2nd attempt.

We set off at 3am from Boulder, heading up to Nederland and then to the Indian Peaks entrance. In the pitch dark, we found a parking spot right at the Mitchell Lake TH and began hiking at 4:15am.

The progress was fast, but slippery (icy) and dark. I took two full out (laying flat on the ground) spills; one fall skinned and bruised my left knee, tore off a part of my right thumbnail, skinned my right forearm, and hurt like hell. That fall pissed me off so much that I cursed out loud at the dark sky and icy ground.

We arrived at Blue Lake at first light and then scrambled to the ridgeline toward Paiute before hiking back to Toll. We arrived at the base of the climb around 7am.

A view of Mt Toll from Mt Audobon. Photo from summer visit to Mt Audobon; background removed to highlight Mt Toll.

We had scouted out the route on the earlier trip and continued to study the “go directly up the ridge” instructions provided by Mr. Roach. We decided to start to the right of the ridge, following a shallow ramp to a narrow ledge. And, since the descent went down the other side of Mt Toll, we couldn’t stash anything. We had to do the rock climbing while carrying our packs full of headlamps, water, food, and anything else we forgot to take out from previous trips. Fun.

Brian led the first pitch. When I arrived at the belay, he was shivering in the shade and wind. The start to my pitch was to traverse left along the ledge toward the North Ridge. Upon reaching the ridge, I found the sun, shelter from the wind, and a great line. I brought Brian over to save his misery, and then I started straight up the line.

The first portion involved climbing up into a dihedral, and then escaping left before the grade became difficult. The climbing then followed a vague line with easy but awkward climbing, simply staying with the easiest terrain. Along the way I found and used (with backup) an old piton. My pitch did not quite get to the “big ledge”. I found a secure anchor that allowed me to sit comfortably in the sun on top of a big block to belay Brian.

Brian took us to the big ledge that traverses right (SW) to gullies for a 4th class ascent to the summit. Brian had other ideas.

Pinnacle on North Ridge (Brian’s Variation). This piece of the ridge can be seen near the top of Mt Toll in the North Ridge close-up photo.

Brian had been thinking that continuing up the ridge line would be the more elegant way to finish. We found a couple alternatives, one or more even looked do-able. Brian picked the most unlikely line: a start on the left side of the ridge (20 feet left) with a traverse under a roof with good pro (small cams) and poor hand-holds (but good feet). We made it, and continued up the ridge-line (Brian estimated 5.8, but I thought it was harder).

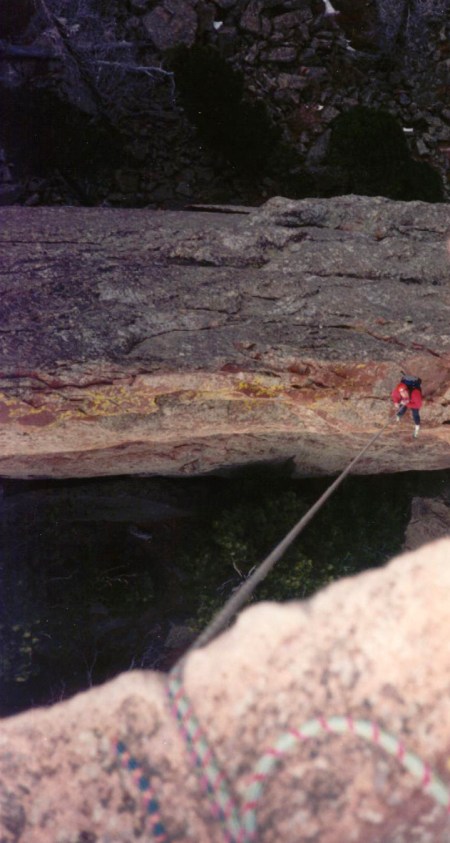

Brian kept his pitch short to stay within earshot of me (the line turned around a corner into the wind). It looked as though we were near the top, but we weren’t. I topped out on the ridgeline after about 30 feet and found a rather large gap between the mini-summit I was on and the real summit of Mt. Toll. I down climbed carefully and then ascended the far side to find a belay at about the same level as the top of the ridge. Since I had not placed gear during the descent/ascent of the gap, the rope stretched across the gap like we were setting up a Tyrolean traverse. I was later sorry not to get a photo of Brian as he popped up on top of the false summit….it was a great image.

Brian quickly scrambled up and we climbed the last 30 feet of elevation to the summit. There we found 6 people lounging in the wind break after having come up the South face (a walk up) after coming over Pawnee Pass. We reached the summit at 11:30am.res

After a quick break and change of shoes, we scrambled and glissaded down the talus and snow slopes to the area just west of Blue Lake, arriving at 12:15pm. Here we rested and ate lunch. An hour later we were in the 4Runner and heading home after another great day in the Rocky Mountain.

And, still, it was not until several weeks later when pointing out to my wife the Indian Peaks off in the distance that I realized that Mt Toll was the unnamed peak. And years later, I still have a special place in my heart for Mt Toll whenever I spot it on the horizon.

Our passion for the Indian Peaks persisted for two years, during which time most of the remaining Indian Peaks summits would fall beneath our boots.

But until recently, I didn’t know how Mt. Toll got its name among the Indian tribe-named peaks. I’d read that the Ute tribe name was rejected for one of the peaks due to already being used to name many geographic features in Colorado. Perhaps it was the proposed Mt. Ute that was instead named Mt Toll, but I don’t know. As far the name, Mt. Toll, I originally thought the name came from Henry W. Toll, a Colorado Senator from 1922-1930; then Brian told me one of his books indicates Mt Toll was named after Roger W. Toll, (the brother of Henry) a charter member of the Colorado Mountain Club and superintendent of RMNP (and Yellowstone & Mt Rainer). It turns out that the Toll family in Colorado goes back to 1875 and produced several prominent leaders who were also mountaineers.

It seems that Mt Toll is well named.