The Diamond.

The East Face of Rocky Mountain National Park’s Longs Peak is the greatest alpine climbing wall in the Universe. Sure, it’s just my opinion, but read on and judge for yourself.

When I started rock climbing some years ago, the Diamond was a place of legend: only the climbing Greats dared challenge the gods with an attempt on the Diamond.

It requires nearly 1,000 feet of high-altitude technical rock climbing in a lightning-filled environment over wet, cold, vertical rock that cannot even begin until completing an approach of nearly 7 miles and well over 3,000′ of elevation gain. And the easiest route up the face requires the skill and stamina to complete two pitches of 5.9-5.10a, three pitches of 5.8, and three pitches of 5.5-5.7 at nearly 14,000′ elevation.

Adding insult to this impossible dream, the easiest route is called, “The Casual Route, ” in honor of Charlie Fowler’s description of his free solo (no rope, no protection) climb of the route in 1978…he said it was “casual” in the sense of…

…not difficult, child’s play, a cinch, easily done, effortless, inconsiderable, no problem, no sweat, no trouble, nothing to it, a picnic, a piece of cake, straightforward, and undemanding.

Uh huh. Thanks for your opinion, Mr. Fowler. I guess that’s one for and one against, as far as voting goes.

Back in the old days, my Midwest climbing friends and I didn’t dare admit having such ambitions; we would only talk about how amazing and crazy some climbers were, and we’d keep our true feelings of envy and aspiration to ourselves. But, over the years, as I grew into a better climber and a mountaineer, I dared imagine that I, too, could climb the Diamond. Someday.

This trip report is about the effort my buddy, Brian, and I made in an effort to climb The Diamond.

Story

Having brought ourselves to thinking that we could really do it, Brian and I decided that we’d use the Spring & Summer of 1998 to prepare our skills, fitness and confidence for a late Summer attempt. During the 4 month preparation, we completed the following alpine snow & rock climbs to ready ourselves physically, intellectually, & emotionally:

- Squaretop Mountain; snowclimb (4/98)

- Mt Belford; snowclimb (4/98)

- Mt. Princeton; snowclimb (5/98)

- Mt. Harvard; snowclimb (5/98)

- Mt. Tauberguache; snowclimb (5/98)

- Mt. of the Holy Cross; snowclimb (6/98)

- Longs Peak via Kieners; snow and rock scramble (7/98)

- The Saber in RMNP; 11 pitches up to 5.9 (7/98)

- Jackson-Johnson on Hallets Peak; 9 pitches up to 5.9 (7/98)

- The Love Route on Hallets Peak; 8 pitches up to 5.9 (8/98)

We had prepared very hard and felt ready to proceed. When the weatherman predicted good weather, we set the date: August 8, 1998.

The overall plan was:

- Hike in the day before to save energy for the climbing day

- Camp in the Boulderfield (to avoid a free solo of the 4th class plus, 320′ plus North Chimney)

- Descend to Broadway Ledge via the Chasm View rappels (3 150′ rappels in the pitch black darkness)

- Traverse the snowy ledge to the Casual Route start, skirting the opening of the North Chimney

- Climb the Casual Route (7 pitches plus traversing finish)

- If unsuccessful, escape via many rappels down the Diamond’s face, and then ascend the Camel Route to reach our campsite

- If successful, traverse the Table Ledge to finish the climb via Kiener’s Route

- Traverse to the North Face Cable Route and rappel back to Chasm View

- Hike back to the Boulderfield to pack up and head home

Before it was over, we’d be sleep-deprived, starved, dehydrated, exhausted, rained and hailed on, surprised, horrified, and delighted.

The Hike into Camp

We started hiking in toward the Boulderfield at 9am. We had all day to cover the distance, so we took our time. We arrived at the Boulderfield and setup camp; and we still had hours to kill.

We wandered up to Chasm View to take in the sights, snap a few photos, and prepare ourselves to find the rappel anchors in the dark a few hours hence. All was proceeding well until we noticed the clouds building.

The weatherman was wrong.

One of the key problems in climbing the Diamond is the weather. It is east facing, so any approaching weather cannot be seen until it is overhead; and with escape only possible via multiple rappels requiring one or more hours to perform, we’d have to move very fast to have any chance. And we’d have to be lucky.

The Approach to the Climb

We arose in the dark and started for Chasm View at 4:15am. Using headlamps, we wandered among the refrigerator-sized boulders, orienting ourselves using the faint outline of Longs against the dark sky.

Reaching the Chasm View area, our previous day efforts paid off with the quick acquisition of the Chasm View rappel anchors. We unpacked the harnesses and the rope and made ready for a descent into a pit of darkness.

I took the first rappel. The light from my headlamp illuminated the canyon walls, but couldn’t reach to the bottom. It was a creepy feeling to rappel into an abyss, but my lack of sleep muted any strong emotional response.

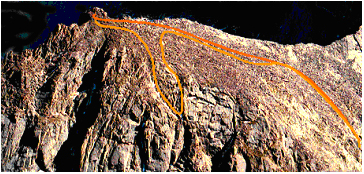

A view of the Chasm View rappel area from the start of the Casual Route; three 150 foot rappels to descend to Broadway Ledge.

My only job besides not dying was to find the next set of rappel anchors. I only had one chance to find them as we couldn’t go back up without losing the day.

But the day started well; I found the anchor. I clipped into the bolts and then unclipped from the rope. I called out for Brian to come on down by yelling, “Off rappel!” Brian stepped over the edge carrying our gear pack, rappelled down and clipped in next to me. After he unclipped from the rope, I started pulling the rope down from the initial rappel anchor while he threaded it through the 2nd anchor. As we neared the end of the process, his headlamp died.

I couldn’t believe it. After 4 months of planning, he didn’t replace the 50 cent batteries. Fortunately, it wasn’t really a big deal. I would just have to find the next two anchors. Although, it was possible that we’d have to wait a few minutes at the bottom of the raps for the sky to brighten enough for Brian to accomplish the traverse to the start of the climb without falling off Broadway Ledge.

I finished getting ready for the next rappel while Brian put the dead headlamp away in our gear pack. I heard him say, “Shit!” With some reluctance, he explained that when he unzipped the backpack, one of his rock climbing shoes fell out and disappeared into the darkness. Now that was a big deal. No shoe, no climb.

If the shoe fell below Broadway Ledge, all the way down to Mills Glacier, it would take us too long to recover it even if we could find it. We’d lose the day. Brian says, “Sorry.” I replied, “Maybe we’ll get lucky; maybe it stopped at Broadway Ledge.” In one part of my mind, I was mad; all this effort wasted. In another part of my mind, I was relieved that we would be going home alive.

But we had to try to find it, so we continued down into the black pit.

At the bottom of the 2nd rappel, there it was. Brian’s shoe had stopped on a small ledge. The climb was on.

We completed the 3rd rappel and then started the traverse immediately. The daylight had begun, and we could see without the headlamps. And we could see that the sky was already threatening. Top of the North Chimney was a loose, snowy, narrow, sloping trap. We decided to do a belay while skirting the rim of the North Chimney and then found “The Ramp” about 20 feet further. At the top of that large sloping ledge, we started the climb with the knowledge that we had to go fast.

The Climb

Pitch 1: Brian gave me the pack and took the first lead up a left-facing corner, and then up and left to a ledge. I followed without incident. We were delighted to see that the weather was clearing. (5.5)

Pitch 2: I took the second lead up a short easy section to the top of a pillar, and then up a tough crack to a belay stance near the start of the traverse. My primary concern was to find the correct traverse starting point. The correct traverse is a protectable 5.7 while the improper one is poorly protected 5.10c. I found it right at a spot with a nice stance. Brian followed quickly behind. (5.9)

Pitch 3: Brian took the traverse. While technically not difficult, crawling sideways is always harder than climbing up. I found it hard to find the best route over the flakes and small ledges, negotiating past wet rock, and trying to keep the gear pack from pulling me off-balance. We belayed beneath a squeeze chimney. (5.7)

Pitch 4: I led the fourth pitch up a short, challenging squeeze chimney, and then up and slightly left on easier terrain to the end of “The Ramp2.” I made sure to continue past the initial piton to give Brian enough rope for a long 5th pitch. Brian followed without incident. The weather started worsening. (5.8)

Pitch 5: Brian then led up a long dihedral and belayed at a grassy ledge. I followed in light rain & hail. By the time I reached the belay, the rain & hail had stopped. We didn’t even discuss bailing. (5.9)

Pitch 6: I took a short lead to the Yellow Wall Bivy Ledge, which was a magnificent ledge for such a vertical environment. I could see how it would be possible to sleep on the ledge quite comfortably. Once Brian arrived, it started to hail and rain again, but this time a bit harder. And then it stopped again. Still no lightning, so we didn’t speak of retreating. We took a short break to give the wind some time to dry out the technical crux of the route.

Pitch 7: The crux pitch. If we could get up this last pitch, we would make it. But failure was still within our grasp: if the rock got too wet or if lightning started, we’d fail and bail. Brian took this lead and moved very quickly. After a short time, the slack in the rope started being pulled up. After 3 quick rope tugs, it was my turn to make it past the several hardest moves of the climb. As I started climbing, the rain & hail started again. I continued up through the wet, narrow inset, and then started up the squeeze chimney. I struggled to get through the chimney with the pack on; when I finally got past it, I was completely exhausted. I took off the pack and passed it up to Brian, then I steeled myself to move past the bulge blocking my path to Table Ledge. Then it was over.

We had made it. I needed a short break, despite the threatening weather; but we couldn’t fail now. We had finished the Casual Route, but we still needed to escape the face and the mountain.

The Escape

Joe sitting on the far end of Table Ledge, preparing to belay Brian to complete our escape from the East Face of Longs Peak

We were sitting on the Table Ledge which we needed to traverse left to link up with the Kieners Route. But the ledge had a break in it, so we had to do a descending and then ascending traverse to find our escape. I started by traversing left past a piton, and then down and left about 25 feet to another ledge called Almost Table Ledge. A wet downclimb is challenging in any case, but at nearly 14000 feet and after hours of climbing, it was very unnerving. I carefully traversed left until I could climb up to the Table Ledge again and belayed off some fixed gear backed up by two cams. Brian followed quickly, and then we continued left, walking along the ledge until we could move above the Diamond onto the north face.

As we stepped above the Diamond, we were shaken by thunder. To minimize our exposure to the elements, we traversed directly to the Cables Route. We were rained and hailed upon, but no close lightning strikes.

After a short hike, we rappelled down to Chasm View, where we had started the day many hours earlier.

The Return Home

It seemed that the entire Boulderfield camp ground was out watching our return. I wanted to believe that it was admiration for a job well done, but there is no doubt it was pity. We felt like and must have looked like the walking dead, as we walked back into camp. One wonderful fellow walked

over to our bivy site with a steaming hot dinner, which we gratefully accepted since we had no food left at all. I had only eaten 1,000 calories during the day, and Brian even less. That Hawaiian Chicken dinner tasted better than any meal I ever had before or since, and it got us home.

Thanks, neighbor!

It had taken us 2 days to hike 15 miles and 4,000 feet of elevation gain, while climbing nearly 1,000 feet of 5th class terrain and descending 600 feet on rappel.

It was and continues to be a great feeling to accomplish such a long held goal.

So what’s your vote?